Steven Levy’s deep dive into Yahoo, “Marissa Mayer Has Completed Step One,” asserts that the first three years of Mayer’s tenure has been dedicated to step one: restoration. Step two is transformation. I believe that having a young and highly engaged user base is crucial to whatever that transformation may be.

The Tumblr acquisition added many young and highly engaged users to Yahoo’s app constellation. esports (organized video game competition) is the next contested frontier for many tech constellations (Google, Facebook, Twitter, Yahoo). For a brief intro on esports , read this.

Google fired the first salvo by announcing YouTube Gaming in June. Facebook followed up by announcing a partnership with Major League Gaming, an esports media company, in July. The next logical step is for Yahoo to launch a central destination for esports, which fits neatly with their mavens (Mobile, Video, Native Advertising, Social) strategy.

Currently, esports is fragmented across the web — reddit, game websites, live streams, twitter, closed platforms with social networks (Steam, Battle.net), etc. Having a central destination, like ESPN, can help onboard new users, retain casual fans, and educate brands and sponsors.

Esports = Tumblr 2.0?

Two years ago, Yahoo acquired Tumblr and its 300 million monthly active users for $990 million. This February, Marissa Mayer stated that the company projected $100 million in ad revenue for the site which now has 460 million monthly active users. Mayer wrote in her Tumblr acquisition post, “the combination of Tumblr+Yahoo! could grow Yahoo!’s audience by 50% to more than a billion monthly visitors, and could grow traffic by approximately 20%.”

Likewise, I believe that building a central destination for esports fans will be an audience growth play. esports could grow Yahoo’s audience by 20% (Base = one billion monthly users from the 2014 10-K, growth = 205 million esports fans based on this esports market research report). And this audience is very valuable to advertisers.

Young and Highly Engaged

The first search result for “esports” in Google is lolesports.com, the esports site for the popular online game, League of Legends. While League of Legends is just one of many games in the esports realm, it serves as a good representation of esports as a whole because it is the biggest and most popular game.

Millennials (18–34 year olds) are a coveted demographic and they are moving to digital platforms in droves. Millennial TV viewers in the US dropped 10% (~2 million) in Q4 2014. Unsurprisingly, Netflix added 4.88 million subscribers in Q1 and 3.3 million subscribers in Q2. Netflix stock jumped up 12% in after-hours trading after each earnings announcement.

This year, Millennials overtook Baby Boomers to become the largest demographic group in the US (75.3 million). Furthermore, Millennials now account for more than one-third of all US workers. With stats like that, it’s no surprise that advertisers covet this demographic.

High engagement is also important to advertisers due to the plethora of entertainment competing for the consumer’s leisure time. Time spent on platform is one metric that represents engagement.

Tumblr users are only second to Facebook users in terms of time spent on their respective platforms according to this survey. If Yahoo is impressed with the average Tumblr user spending 34.2 minutes per day on the platform, they should really be impressed with esports fan data.

The average Twitch user watches 106 minutes of content per day (triple of Tumblr). And that’s just the average user. Power users (~58%) spend more than 20 hours a week (2.8 hours per day) watching streams on on Twitch. That’s roughly the amount of time (2.8 hours per day) the average American spends on on watching TV in 2014, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS).

The esports fan base is a younger, more engaged, and more male version of Tumblr. They are moving away from print, radio, and TV and moving to the internet and mobile. Closing the gap between advertising spend versus time spent on mobile is roughly a $25 billion dollar opportunity in the US.

Strong Growth in Mobile Advertising, Native Apps Prevent Ad Block

KPCB’s 2015 Internet Trends Report presents a strong argument for mobile advertising growth on a macro level:

- Global mobile population penetration is 73% versus 39% for internet penetration

- Mobile advertising is under-indexed relative to time spent: 8% of advertising spending versus 24% of time spent

- Mobile advertising growing at +34% Y/Y versus desktop, growing at +11% but decelerating

Micro level data tells the same story. Tumblr’s mobile app monthly users grew by 32 percent in 2014. Twitch’s mobile figures (including browser and app uniques) grew at a CAGR of 174.36% from April 2012 to July 2015. Twitch launched it’s mobile app in April 2012 with 573,566 monthly uniques and last month, that figure was up to 15,244,998, according to quantcast.

Another great thing about mobile is that native apps prevent ad blocking (for now). Ad blocking is such a big problem that according to Darren Herman, “we are three clicks away from an ‘oh shit’ moment for the web.” Since eSports fans are tech-savvy, it comes as no surprise that the gaming site category have the highest rates of ad blocking.

Content consumers “pay” for content by viewing ads. But if they block it, how can content creators make a living? Since Hank Green is causing a stir with Facebook this week, it’s timely to look at his suggested monetization model for content creators — “Just Ask” model, which is popular with eSports content creators and their fans.

By my count, sodapoppin was the seventh most popular Twitch streamer by subscriber count as of July 2015. To the left is a list of people who have donated money to him. The top person has donated over $50,000. Yup.

Here’s a video of sodapoppin receiving $7,639K from Twitch user Amhai during a stream.

Why is this happening? Because digital stars, especially those who focus on gaming content, are more influential than traditional Hollywood stars among US teens.

Top Three Influencers for US Teens are YouTube Stars Focused on Gaming Content

Variety conducted a survey on US teens in 2014 and found that ten out of the top twenty figures most influential to teens were YouTube stars. The survey was conducted again this year and the top six figures are YouTube stars (KSI, PewDiePie, VanossGaming, Nigahiga, Smosh, and Markiplier), of which the top three are focused on gaming (KSI, PewDiePie, VanossGaming).

Gaming plus comedy seems to strike an algorithmic chord with a global audience. While these influencers focus on gaming, they don’t focus on esports. Why?

To answer that question, we need to answer these first:

- What is an esports influencer?

- Should esports influencers become YouTube influencers?

- Can esports players become YouTube influencers?

- What’s the opportunity for Yahoo?

What is an esports influencer?

An esports influencer is someone who derives their followers mainly through their history of playing video games competitively. As of July 2015, only two of the top twenty Twitch streamers are active esports players (Bjergsen and Dyrus) and two are retired esports players (TheOddOne and imaqtpie).

The paucity of esports players in the top streaming list is due to the fact that pro players have to practice and compete which takes up most of their day. Ironically, the intensive demands of being a pro player sometimes results in a weird compensation model: players could make more money by purely being a streamer rather than play for a professional team.

That’s like saying Michael Jordan should just stream himself playing pickup basketball games with his friends rather than play for the Chicago Bulls.

Should esports influencers become YouTube influencers? Yes.

YouTube influencers have become mainstream and brands know how to work with them. Virtually every top YouTube influencer is represented by a multi-channel network (Fullscreen, Maker Studios, etc.) with a huge sales team. Some influencers are even getting picky about their endorsements.

Onboarding esports influencers to a central destination for esports would be critical for Yahoo. Advertisers are more likely to partner with esports influencers with the metrics and campaigns they are familiar with — YouTube influencers.

Can esports influencers become YouTube influencers? Maybe.

Most esports influencers receive some level of media training. They are aware and careful of what they say or do during streams. Media training is important as evidenced by a popular Twitch streamer being banned this week. trick2g, the eleventh most popular Twitch streamer, was banned for staging a fake swatting on himself. Swatting is the act of tricking an emergency service (usually involving the police and/or SWAT units) into dispatching an response based on the false report of an ongoing incident.

YouTube influencers have to tread a fine line between pleasing brands (“selling out”) and pleasing fans (being cool). Not every esports influencer has the desire or capability to step into the next stage. Some of them are content just streaming, saying whatever is on their minds, and getting $50,000 donations.

What’s the opportunity for Yahoo?

YouTube is going to be the dominant video sharing platform and that’s fine for Yahoo. Help esports influencers build up their audience on YouTube and then create exclusive content for Yahoo. This is an example (more) of exclusive esports content.

After all, content is king. If House of Cards or Game of Thrones was exclusively on Hulu, I would have a Hulu subscription. You would too.

Most esports influencers have a small YouTube subscriber base which is why they aren’t getting much attention from multi-channel networks. Yahoo should step in to fill that void. Once they build a sizable YouTube audience, focus on creating exclusive content and monetize that through native advertising.

What if advertising is just going to be more expensive and less scalable?

Jeffrey Rayport asserts in his article, “Is Programmatic Advertising the Future of Marketing?”, that,

“Soon, every display will be an addressable medium — that is, each will be individually targetable by device and, in many cases, down to a specific user; and interactive displays will not only deliver ad messages but also track consumer response. The result is a new era of marketing accountability, in which advertising ‘budgets’ will have turned into marketing ‘investments.’”

I hope that this isn’t going to be the only model for the future of advertising. What if advertising is just going to be more expensive and less scalable? What is wrong with that? While native advertising is less targeted, it is great for brand equity. I understand the importance of demonstrating ROI for brands and advertisers but include some brand equity valuations (albeit fuzzy) on top of CPM rates.

Humans love storytelling and the best brands tell stories. Look at this Swedish tannery’s website for example. It’s chock full of stories, information, and brand heritage. Isn’t that so much better than programmatic advertising — some ad that was specifically served to me because of my demographics or past purchases?

Let’s look at two compelling native advertising examples from this year that could serve as a model for esports content: the “StartUp” podcast’s marketing campaign with Ford and Esquire Magazine’s What I’ve Learned feature on Medium. Here’s a New York Times article on native advertising on podcasts and Esquire’s editor’s note on the collaboration with Medium.

If you click to 11:50 in this podcast, you can hear an interesting story about a Human Factors Engineer at Ford and then it directs you to go to www.ford.com/startup. What the heck is a Human Factors Engineer? That piqued my interest and I went to the link. I was interested in that story and started exploring that site because nothing was directly about buying a car. Even though I didn’t run out and buy a car from Ford, my view of Ford’s brand has definitely increased.

Similarly, my impression of Microsoft’s brand has been elevated by a notch due to the What I’ve Learned series. I’m sure Microsoft could have been more efficient if it used programmatic advertising and bid on ad exchanges to find the specific people to advertise this to for the best price, but they didn’t in this case. As a reader, I was able to consume all the content without distraction before I saw this ad.

Consider how this model could work for Microsoft Edge, their rebrand of Internet Explorer, with Yahoo’s help. The esports demographic is exactly what Edge needs — young, highly engaged, and generally early adopters of technology. This is the demographic that put IE in its grave in the first place. Microsoft could sponsor high quality esports content through native advertising to increase its overall brand equity. Since self-deprecation didn’t work, try being cool. If Microsoft is cool, that demographic would be more inclined to give its products a shot.

Currently, there is lack of a high quality content publisher in esports. Reporting is rarely critical because criticism can lead to denial of access. Long-form pieces on esports are few and far in between: the New York Times wrote a great piece in 2014 and ESPN The Magazine published an issue solely on esports this June (check out the featured article here). There is an opportunity for Yahoo to create high quality esports content through the launch of a fourteenth digital magazine, “Yahoo Esports,” or at least a new series for esports mimicking something like MLB Condensed Games.

Create great content to get users to come and build great social features to get users to stay.

Build Low-Resource Voice Chat Software, Migrate Yahoo Empire

The low-hanging fruit in social is daily fantasy sports, which has been blowing up. Last week, DraftKings announced that it received $300 million in financing. Three weeks ago, FanDuel announced a $275 million Series E round. According to their websites, DraftKings guarantees that it will pay out $1 billion this year; FanDuel guarantees $2 billion.

Will daily fantasy esports be as big? The two players in fantasy esports, Vulcun and AlphaDraft, have paid out $6 million and $5 million this year respectively, according to their websites. Yahoo already has a daily fantasy site, why not make one for esports as well?

Esports daily fantasy would just be the first step in social for Yahoo. More importantly, Yahoo should build a low-resource voice chat software (PC and mobile) and migrate the entire Yahoo empire onto it.

I thought of voice chat after reading a piece by Dan Grover on Chinese mobile app trends. Chinese mobile apps have been expanding in services (payments, food delivery, taxi services, etc.). In the US, the trend has been the opposite — single function apps. I never thought that voice chat could serve as the centerpiece of a constellation versus a messaging platform (example: messaging apps in chart below). But it does, and an example of that is the Chinese company YY.

YY started off as voice chat software for gamers in 2008 and has transformed into video-based social network. Think Twitch but with much more social features and karaoke. YY’s stickiness in voice chat is so strong that even Tencent, who owns the largest stand-alone messaging app in China, WeChat, can’t displace it. For more on WeChat, read this article.

Last month, Tencent’s subsidiary, Riot Games invested $30 million in Curse to support their eponymously named voice chat software. This could be part of Tencent’s “pan-entertainment” strategy which seeks to tie in all of their businesses into the mother-of-all constellations (PC and mobile).

Fred Wilson writes, “If you own a leading constellation, you can use your apps and your relationship with the users of those apps to promote and distribute new apps that you either build or buy.” Yahoo is one of a few companies that has a leading constellation. Building a low-resource voice chat software is a great way to attract esports fans.

Building a central destination for esports is a huge opportunity but also a risk as development resources would have to be shifted from other projects. I think that risk is well worth the potential 20% increase in an audience coveted by advertisers. Tencent and other Asian tech companies understand the growth of esports and are on it. In the West, Google and Facebook started making moves this summer and they are moving fast.

Yahoo, don’t be left behind.

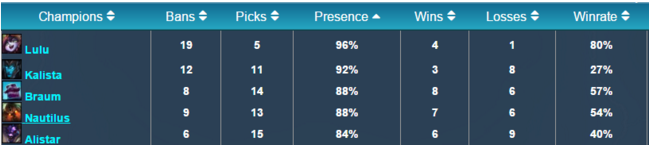

IEM Highest Pick/Ban Champions

IEM Highest Pick/Ban Champions

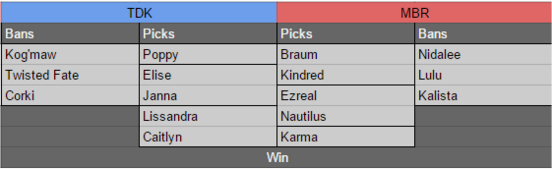

Proposed Game 4 Draft

Proposed Game 4 Draft